How some of the world's poorest people are managing their money better than many of us who have lots of it

Moshi, Tanzania: The men were gathered in the open courtyard, most of them seated on cheap chairs facing a table. Six more, clearly in a leadership capacity, were seated behind that table. Every so often, a man from the audience would get up, hold a bill (usually a two-thousand shilling note, worth about a dollar US) for all to see, then take it to the table. He would hand that to another man who also held it up for all to see, then place it in a box in front of him.

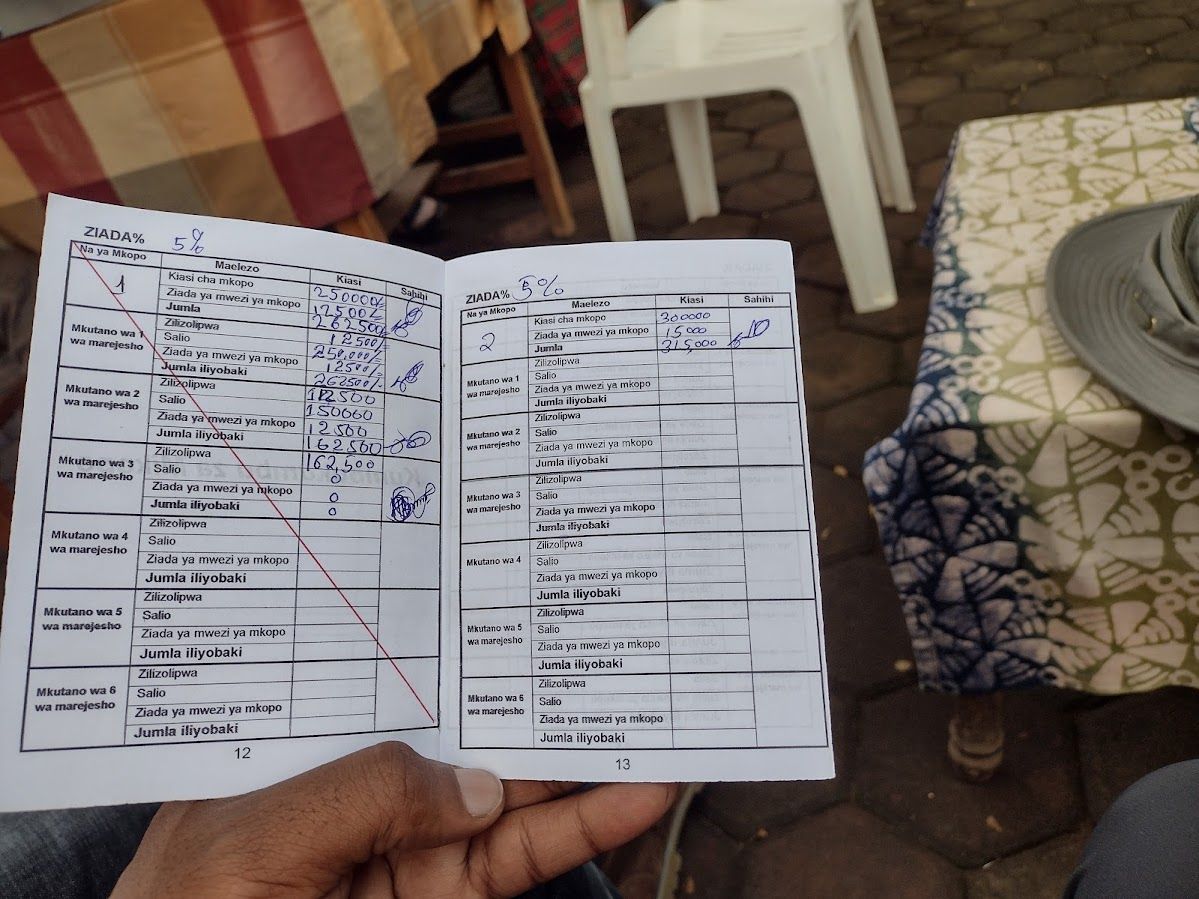

This was regularly repeated, as were several other ritualized procedures, including the handing out and marking of individual books which were clearly passbooks with financial history on them, all in a lively discussion in Swahili. Cocaya, a lovely Tanzanian woman, translate the rapid-fire discussion so that I could keep up.

I was watching some of the poorest people on the planet, porters who work on Mount Kilimanjaro and many who are also subsistence farmers, taking control of their money, and running a VSLA (Village Savings and Loan Association).

A VSLA is a formalized, small banking system which allows people to take out micro loans without needing access to a banking system. They are, in effect, their own bankers. You and I might be familiar with the micro-loan program but the VSLA is different. It builds savings wealth and teaches money management and responsibility to millions of people worldwide.

To understand more please see this:

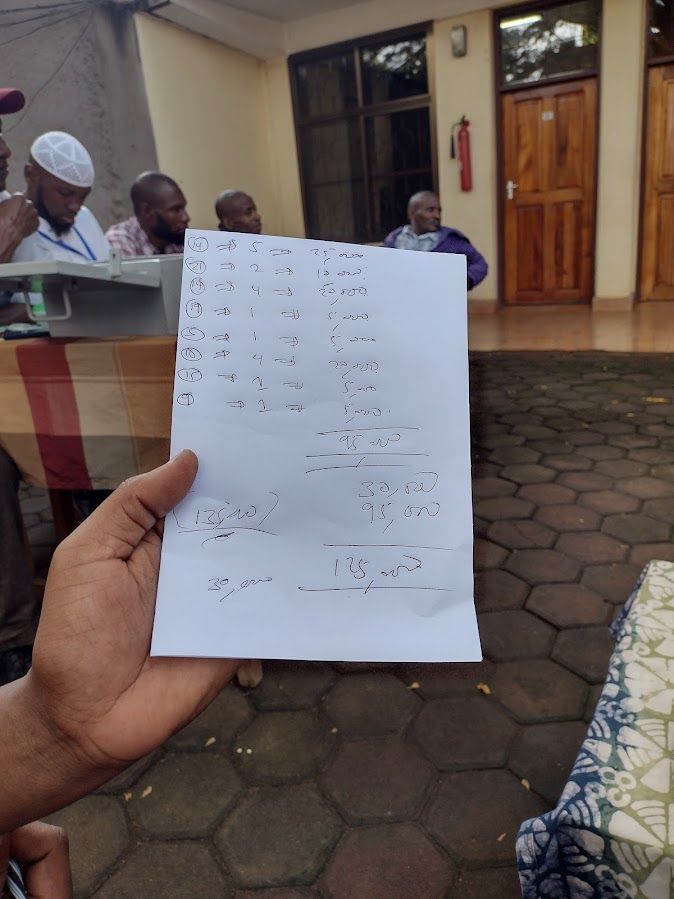

Currently, four different groups of porters meet weekly in nearby cities like this one in Moshi, and they put $2k shillings into the "bank." Each week they are required to know the precise balances in the two separate pots of money which they are growing, managing and borrowing from. If they don't, it's a .25-.50 penalty, which goes into the communal pot, noted and chuckled about.

Everyone has likely forgotten those balances at some point, but those fees add up, too, when you are living on such low wages. Being tasked to remember emphasizes the importance of knowing how much money you have, what is available to you and others in the group, and to acknowledge the size of the pot as it grows over time. It teaches you to notice how much money you've grown, who has borrowed and who needs it, as well as who is paying it back according to the rules.

After all, this is in part YOUR money, and someone who borrows and doesn't pay it back on time is affecting YOUR wealth, as well as others' access to that money in case of need. It teaches you to be mindful of your money, where it goes, who is using it. How many of us can say that?

Back in the 1960s, American television used to pose the question to parents at ten eleven PM:

"Do you know where your children are?"

These days, asking the same thing about your money is just as important. How many of us knows precisely what we have in our bank accounts, checking accounts? How many of us, who likely earn a great deal more, are in touch with the flow of cash and funds through our lives?

There's an important lesson here, given our profligate spending, made possible by credit cards and easy access to money. When there is so little, learning to manage it means everything.

Here, these men and women are pooling their funds to allow them to take out a micro loan once a month, They have three months to pay it back at a low interest rate. This kind of accessibility can make all the difference when someone has a family emergency or wants to buy a cow to start a small business.

Last year I interviewed five porters who had undergone budgeting training which had been offered by the Kilimanjaro Porters' Assistance Project (KPAP). Each of those men had transformed his life, and the lives of his family, by changing his relationship with the funds he'd been paid at the end of a hiking trip.

Some twenty thousand porters work the mountain, some more often than others, and their pay can vary widely depending on the company which hires them.

However, at the end of their trip, from the moment those porters (male and female) leave the slopes of Kilimanjaro and begin their journey home, temptations await. Women, booze, clothing, food, all manner of distractions leak their funds until by the time they get home, their pockets are empty.

You and I both know folks like this. Perhaps we have similar habits. If you're always broke, this is a wake-up call. This representative group of five men of varying ages, some close to ending their climbing careers and others just beginning, had completely retooled their lives by just learning a few better habits.

As a result, all of them had new businesses, some had wives who had sidewalk food services, some had bought a cow or a goat. In all cases, each man and his family was no longer solely dependent upon climbing for a living. Their lives were utterly transformed by just a few basic habits.

If you're interested, that story is here.

KPAP initiated this project at the urging of Ben Jennings of Peak Planet. Jennings had created a VSLA in Cameroon while working in the Peace Corps and he saw how empowering and powerful the creation of wealth among the desperately poor could be. As a very active member of KPAP and a strong supporter of porters' rights, Jennings saw that especially due to Covid and the additional challenges the pandemic caused with tourism slowdowns, teaching porters financial discipline would be a lifeline.

The men sitting at the head table are voted into those positions by the group and include a Chairman, Secretary, money counters and the box keeper, who manages the many padlocks on the box that holds their collective funds. These are positions of high trust and respect, but the group members are encouraged and expected to question and challenge what they're doing and how. After all, it's their money. There is a constitution which drives how the VSLA is run, but it can also be challenged if deemed unfair.

For example, one man complained that the constitution didn't allow for him to draw money that is earmarked for immediate family until a child has died. He wanted to know, not unreasonably, why he couldn't draw those funds to prevent his child from dying in the first place.

These kinds of questions arise when people take personal ownership of a collective endeavor. Those questions and challenges speak not just to the individual, but the rights of the whole, all of whom have a stake in the use of the funds they so diligently work to build.

The transfer and passage of all the money, no matter how small, is formally acknowledged in a way that builds trust. Everyone can see who brings money in, everyone can see and hear who takes money out and for what. In this way all the members have a stake in the process.

Then porters can have someone else bring their money, if that porter is indisposed or working, for example, or has to take care of a sick relative. The porter member can also take out a loan on someone else's behalf. This again reinforces cooperation and community. The money offered for someone else is formally registered in their names for all to acknowledge.

The group is asked if anyone needs money, and for what. Their constitution defines the rules, especially when it comes to taking out funds for health issues or death in the immediate family. In this way, the community not only knows what's happening in a member's life, but their funds are being used to help that family member survive. Or, in case of death, properly grieve.

At the time of this meeting, Lucas Mayoba, who is the Coordinator for the VSLA, told me that there was 1,018,000.00 TSH already in the social fund for the group's use. That's a total of $436.62 US. For these people that is a princely sum indeed. But that's hardly all.

There is another fund for loans. Each member purchases a share in that fund, which costs them 5000 TSH (2.14 USD). Every week they can purchase up to five shares. Right now, that fund has close to 3.5 mTSH, or $1501.05 USD. Again, a very significant fund, considering their wages.

This might strike you as an awful lot of formality over such a pittance. However the process for people for whom money is so fleeting and so hard to hang on to, the formalization of these exchanges elevates their earnings where it needs to be, because in doing so they learn to treat their funds with respect.

They also learn to respect other VSLA members who take out loans and pay on time.

Lucas is the KPAP representative. He oversees the community-based trainers (CBTs) to ensure that the VSLA's constitution, rules and regulations are followed. Because the organization manages other people's money, it has to be legally registered locally.

Sometimes, this leads to misunderstandings, he explained. When he was registering the VSLA group in one community, a local official didn't understand with the VSLA and how it worked, and wanted to impose their own constitution and group functioning methodology. This is common where people don't understand such organizations, and is part of the challenge of setting them up.

The whole point with a VSLA is to ensure that the power and all the money that lives in the padlocked box stays with the VSLA and the porters who regularly discipline themselves to put their meager funds into that box.

By now, what's in the box is already substantial.

In just the Moshi group, they have saved the equivalent of about two thousand US dollars just since the group formed on November 17, 2021.

If these hardworking men and women, struggling to make a living as porters, can manage to save this much through cooperation, discipline and being mindful of their money, I have to ask what we might learn from them.

I would say, we could learn a great deal.

Comments powered by Talkyard.