Or, the joys and challenges of ancient farm life, combined with the breathtaking generosity of the Mongols

I woke up to the sound of hoofed feet, a lot of them, right outside my tent. The September morning in Western Mongolia was only moderately cold, but still cold.

You have to redefine cold in Mongolia, especially as fall slips into early winter. We were still having lovely, sunny, 70-ish days, but the mornings were beginning to get an edge to them.

So. First things first. To wit: shit.

No, not that. If you want to get warm, if you want to eat, wash, drink tea, you have to get shit. Lots of it. Mostly cow, some horse, but mostly the flattened, dried patties that are scattered in the sun in all directions. Odorless, and superb fuel. The very definition of sustainable sourcing.

Get up and gather, before the sun comes up. In my case, part of how I showed my gratitude to my hosts was to take this daily task off their hands, and ensure that yet another big white bag of cow patties had been loaded up for the day’s fuel. That, and in this part of Mongolia, the dry thorn bush sticks that serve as kindling. There are no trees here, just these bushes. You have to walk through them, ride through them, push through them and get regularly perforated. Their leaves and buds are essential food for the herds of goats and sheep which provide food and income for these people, and the dead branches provide us with tinder.

And tender fingers after a while.

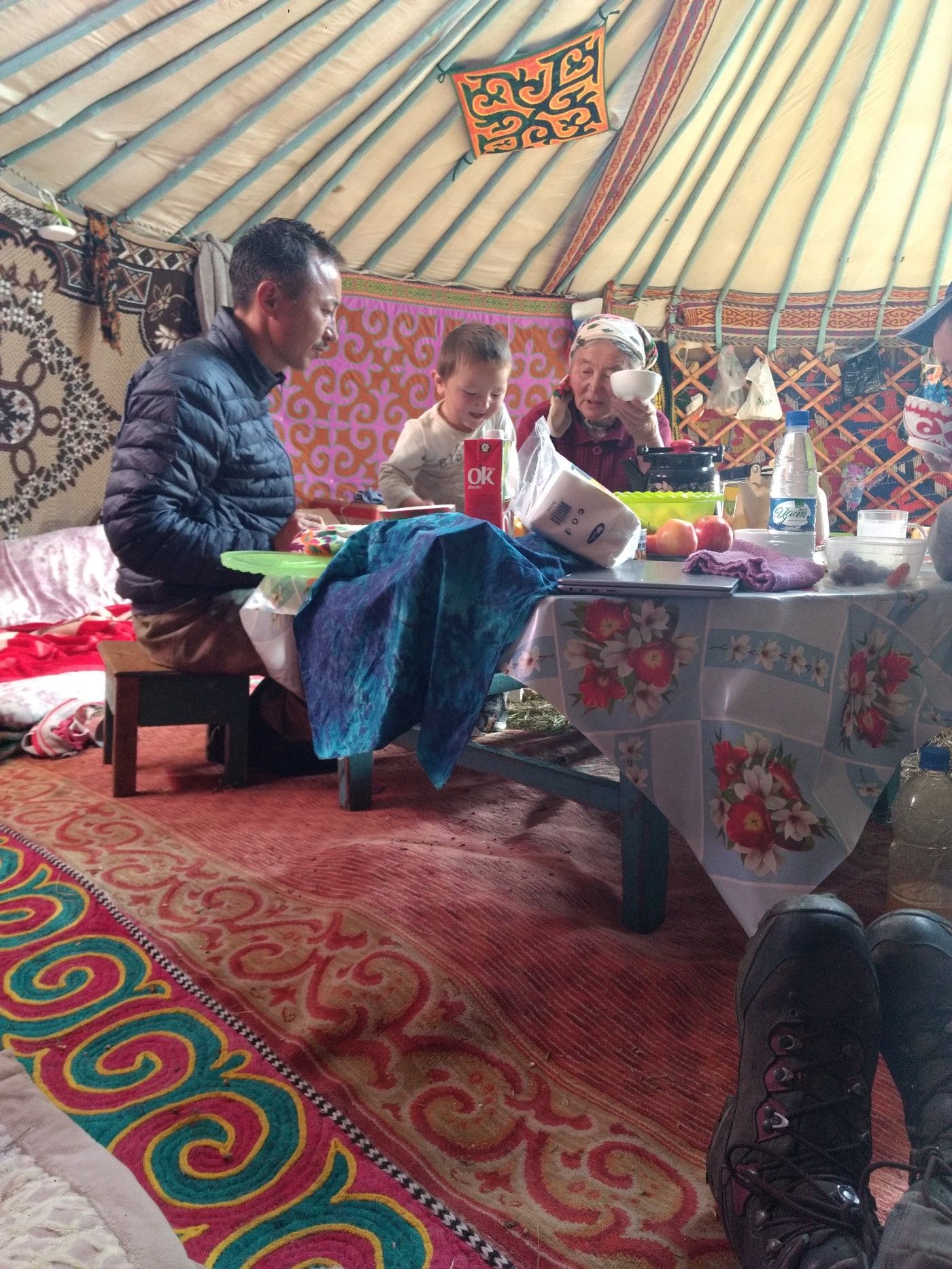

Seku, who was my host on this homestay, had met me at the airport. He’d been a guide and translator (he is self-taught and his English is superb) on a trip that I’d taken with the same company , Zavkhan Trekking, to Kazakhstan in 2017. Seeing a familiar face at the airport in a country where English is sometimes rare was not only a godsend, but a delight, as Seku was beside himself delighted to share his family with me.

I had requested that Zavkhan design a custom trip whereby I could explore and experience the culture and the country first hand. Seku’s house and village were my first of two homestays. I was in for a serious treat.

We had stopped at a local market for supplies, then his younger brother drove us the bumpy two hours on rocky clay roads to his village. We would stop regularly to pour water his overheating engine, then stop at the river to refill the water supply, douse the engine again, then limp along until we arrived. This is a horse culture. While motorcycles are making inroads, horses are in many ways far more efficient, and don’t need to be doused regularly. Just watered and fed.

Seku’s apple-cheeked, 72-year-old mother Jazira ran out to greet me as soon as I arrived. She was in tears to welcome an American guest, and she enveloped me in her strong embrace. Soon my luggage was scattered along the perimeter of the large ger, which is the white, round nomadic house of the Mongols. The floor was the raw ground, as this large structure is folded up and moved regularly as befits the nomadic lifestyle.

The younger son’s smaller ger was right next door. The family was building a new home in the nearby village of Altantsogts, so they were back and forth constantly, while also managing a herd of some 400 sheep and goats. Cattle too, which had to be milked daily, as did the goats.

Seku was eager for me to get the lay of the land, and to find a role in the family’s daily events. As a farm girl, that turned out to be easy. The daily chores of herding the animals (by small Mongolian horse) and helping wash the endless flow of dirty dishes gave Jazira more time to rest, which she richly deserved. Three young kids were in and out all day long, and their demands on her time were exhausting. She would regularly, as did we all, head out into the fields to gather firewood and dung, and cart water back in an enormous yellow jug that she balanced by rope on her back.

I was shocked when I lifted it. I don’t know many 72- year-olds in America who could do the same thing, day after day. It had to weigh about 65 pounds.

Seku’s sister-in -law began each day almost as early as I did to milk the cows. She was the one who taught me where and how to find fuel.

Because I am a light sleeper, I set up a tent in the nearby thorn bushes, as the kids were forever coming over and the family was bustling in and out. Seku’s family was very gracious about it. I was up very early, before four am most days, which allowed me to gather the essential wood and dung for both gers and enjoy the sunrises, which were spectacular.

For Westerners accustomed to all the conveniences, staying with a Mongolian family in a ger could come as a bit of a shock. Our “toilet,” such as it was, was nothing more than a hole in the ground a decent distance from both of the gers. If all you had to do was pee, pick a bush. The kids went everywhere, until they were old enough not to fall into the long drop. Our wash station was just outside the ger. Nothing more than a piece of board, a kettle with water from the river and a bar of soap.

Most folks wash once a week in the river. It’s cold. You don’t linger. I had one bath, for which Jazira kindly warmed a lot of water. I set the green tub and the board behind the ger away from most human traffic, stripped, and did my best to remove the grit as the brisk wind raised goosebumps. I didn’t know it at the time but that would be my last wash for almost three weeks.

I was, as everyone else was, always dirty. The constant work with animals, the dust and wind, and the daily chores served to keep me grubby. I washed my pants and shirt twice, then hung them on the tight ropes that encircled the ger. The high, dry climate and constant winds had them dry by sunset.

Maintenance of the structure of the house is constant, for the materials are of the earth and they disintegrate. For example, a certain kind of tall weed serves as part of the structure’s external support system, and they have to be sewn by hand into the ger. It’s slow, painstaking work and it never ends.

Below, Jazira with a handful of the weeds for the ger, and how those stems are sewn into the structure.

People’s lives in the countryside revolve around family. The grandkids would fight to sleep with Jazira, who would wake up first and leave her living “hot water bottles” sleeping peacefully in the dense warmth of her bed. This gave their own mother a much-needed break. Each day Jazira would take one or more kids by the hand and walk them around the area while she gathered wood or water. Jazira’s work was on display around the circumference of the main ger, and she took a few hours to teach me how to sew.

And, she gave me a few pieces of my own, which saw daily use thereafter, as colorful mats to brace my knees on icy mornings when I crawled out of my tent onto the open steppes. I never saw anything as colorful as her work with other artisans, and those mats have pride of place in my house. They are where my feet land on the otherwise cold wood floor of my bedroom in Denver, reminding me of her generosity. In return I gave her a pair of 3.0 glasses, which for her failing vision allowed her handiwork to swim into focus for the first time in years. Such simple gifts can have such lasting impacts.

Seku, who is still a bachelor, is regularly pressed by his mother to get married and start producing progeny, Mongolia hands out Good Mother medals to women who have three or four kids. In a vast country with only a few million people and vastly more animals, there is plenty of room to expand. However those very empty expanses are part of what makes Mongolia so mesmerizing. Besides, far too many kids eschew the hard countryside life for Ulaan Bataar, which is growing at blinding speeds.

Out here, the gathering of wood is matched only by the constant gathering and preparing of food. Milk and meat products dominate; boiled mutton is served three times a day. Bowls of a variety of cheeses and milk foods, those which have to be able to survive without refrigeration, are served at every meal, and have to be regularly replaced. That means that there is never a time that a bucket of yogurt (like you have never had before) or some kind of milk delicacy isn’t being processed inside the ger. Neighbors and friends stop by constantly, are given food and hot Kazakh tea, and then they are on their way to find the horses that have disappeared into the brush.

The whole point, however, is not just to be in Mongolia, per se, but to experience the real Mongolian way of life. Not just to visit the Eagle Festival (of which there are many, with plenty of Western tourists) but to see how people prepare, at home, for competition, in one of the only two countries in the world where people still hunt for eagles to feed their families.

Whatever they may have on hand is yours. The generosity is legendary, but you really have to experience it to understand the lengths to which these remarkable people wish for you to feel at home, part of their world, well-fed and emotionally nourished.

The real Mongolia is populated with people like Seku and his family who are eager to share their way of life, laugh with you when you make mistakes, and help you experience a culture that is truly rare: one of the last great horse cultures in the world, and people still living far outside the reach of most modern conveniences. Most of us Westerners didn’t grow up on a farm. Most have no idea what it’s like trading a handy spigot for having to schlep heavy containers of water from the local river to the house. These things have a way of enriching our understanding of the conveniences we have, as well as reminding us of how good it feels at the end of the day to be able to measure the day’s work in piles of wood, bags of fuel, water for the morning’s fire, and a large herd of goats and sheep quietly chewing as they settle down for the night after milking time.

When it was time to say goodbye, I had amassed so many impressions and so much warmth for this remarkable family that it was very difficult to leave. I hugged Seku’s sister-in-law in the middle of her morning milking, and she was emphatic in her thanks for the daily help. Jezira was beside herself, and Seku admonished me that I must come back (I plan to) and that I had to consider myself his sister.

Some time later, after Seku had headed off to a translating and guide job, I was at the Uglii Eagle Festival with other Zavkah clients. I heard “JULIA!!” behind me. There was Seku, beaming broadly. How he found me in that teeming crowd, I’ll never know. But we embraced like long-lost family members. I was nearly in tears with delight and so was he.

After a few moments of catching up, he had to return to his client. As we hugged again, he said, “I love you, Julia,” meaning it.

Priceless.

Is a Mongolian homestay for you?

It depends. Do you want to be fully immersed in real Mongolian ger life?Do you want to feel like an honored member of the family? Do you want to leave your world behind and be welcomed into another, with open arms, and experience a simpler, happy life? Do you want to feel so connected with people that when it’s time to leave, it’s also time for tears?

Then perhaps this is for you. Ger life isn’t for everyone. But it is for those who want extraordinary and rewarding experiences, out of the ordinary, and life-changing relationships.

And just in case you were wondering, this kind of trip really is for everyone. At nearly 67, it was perfect for me. It is in fact perfect for any adventurous soul or souls who doesn’t want the same old tired hotel room, just a new city and folks with a different accent.

This is an experience. And you’ll never forget it.

Comments powered by Talkyard.