A mighty dream takes flight, and may just change the world in its own way

The open air studio was in a pleasantly-treed complex, just downhill from the well-tended walkway. I had been driven out close to the Arusha airport to visit some kind of design center. At this point I had no idea who or what I was visiting, just that my safari operator, Etrip Africa, had lined up an interview.

Given my long history with Ben Jennings, my operator, I was in for a treat. You'll understand why in a moment. Mostly know this: Ben has a wonderful habit of finding people, companies and organizations focused on solving problems, not creating them.

However, initially I was very confused.

As I walked into Dunia Design's studio, I saw high-end furniture. A pricey designer showroom. Tables, chairs, couches, a bed. Book cases and more, with swatches hung on the far wall, and planks of wood in various colors on the floor. Gorgeous beaded chandeliers.

What on earth is an uber-expensive furniture design showroom doing in Arusha? Was this exclusively for well-to-do mining executives, government officials and ex-pats?

Julia Pierre-Nina, a lovely, dark-haired young woman and the company's designer, greeted me.

"You're looking at garbage."

Excuse me?

All the pieces of furniture, whose equal I have seen in many a five-star hotel, were made of low-grade plastic.

You have to be kidding me, I thought.

Julia smiled at my expression. She's used to that reaction by now.

Alexis Cronin, an architect by profession and part of the team which is behind all this, wandered over from the office and sat down next to us.

On another expensive-looking piece of gorgeous "garbage," I might add.

Alexis and Julia gave me the back story. Bearded and lanky, a sweater tied around his neck, Alexis didn't look like a furniture guru. He is, along with their entire small but dedicated team.

Alexis explained that he and his wife Evanna Lyons, who is a psychologist cum tree hugger cum Greenpeace type, had arrived in Tanzania around 2012. The plan was to build a church, stay three or four months, then return home.

Life, ideas and a touch of magic got in the way. It began with a heart- to- heart about building a business together. Evanna's deep commitment to the environment was part of the driving force. As Alexis said, having their first child was the other.

There's nothing like having kids to whom you would rather not bequeath a planet layered in trash. The question they posed:

‘How could one take this ever-increasing, indestructible waste and turn it into something beautiful with purpose?’

"Clean environment, clean mind," he said, smiling. They saw plastic bottles everywhere, filling streets, dumps, rivers, landfills. No end in sight. Someone has to do something, says everyone. Too many of us don't think, and another bottle or two land on the streets every day, all day, ad infinitum.

How it got started

First, the name. Dunia is a Swahili word meaning earth, world.

Dunia Designs began as low-tech as it could get, starting around 2015-2016. People gathered recyclable trash, the trash made its way to adapted machinery. The operation grew, machines improved, processes improved, a passionate and dedicated team coalesced and got focused. They were willing to bootstrap the operation until it bore fruit. That's the very short version.

From humble beginnings, the process has become far more sophisticated.

This video shows the process by which the product is produced.

In addition to cleaning up plastic garbage, local people are trained in high-end skills. Tanzania, as with many African countries, needs industries which can train and employ. What better way to do that than with ecologically- sound products?

"We went from our iconic pooffe to a couch to a coffee table," Alexis said. Julia, who is Tanzanian-born to German and Mauritius parents, and another director, Elaine Mahon, steered the company towards more sophisticated items.

The heart of the product which makes the framework is what's called "greenwood," Julia said. From their website:

In order to create greenwood, plastic waste is collected from streets, rivers, oceans and rubbish dumps. It is then cleaned and shredded before being put into an extrusion machine which compresses and heats the waste to form a greenwood plank. These planks are then used by our carpenters as a wood-substitute to create beautiful furnishing pieces.

That's what I was looking at on the floor, in varying colors. Not wood, although at first glance it could have, and did, fool me. That's the beauty of it. I saw that same greenwood in the reception area of Lemala's Ngorongoro Tented Camp and their Mpingo Ridge Lodge in Tarangire National Park.

Julia describes Dunia as a social enterprise.

"An increase in the bottom line correlates directly with positive environmental impact," she said. "Our products are developed with a focused on quality, and beautiful design. Only in this way can it be a viable, competitive product."

You wonder what kind of world we might have today had most corporations begun with that framework, keeping the environment and people in mind first.

"The design needed to take into account a positive impact but with a viable product," she continued. Here's the part I like best:

The bigger the company gets, the more trash is recycled into furniture.

The more people buy their furniture, the fewer trees are felled.

The more furniture is made all over the world, the more plastic is recycled, and the less pressure on the environment.

Again, to say nothing about local people who are trained and employed in the company, which as it grows, employs more.

To better understand how this works and how Dunia has developed a formula to gauge how much benefit a single furniture item can benefit the world, please see this:

That said, they have a mind-bendingly big job ahead of them. At one point, Alexis told me, they took on a math problem. How much plastic garbage is there? Really? How much is actually recycled (in the US, in 2018, just 8.7%) And how much of a difference are they making? Really?

The result is one of those discouraging infinity numbers. It's enough to make you give up and go home. Dunia didn't.

But we're ahead of the story.

Dunia's team is of the Millennial generation which is tired of "green-washing," or environmental brainwashing. In the US and elsewhere we have been subject to that very thing for decades, as huge oil and other polluting companies pitch massive PR campaigns to redirect the narrative around who they are, what they do and what they stand for.

Then there is a bumper crop of product slickly billed as eco-friendly, when they are most certainly not. In those marketing, takes precedence over making a difference, which is harder, takes more investment and effort, but pays off big in the long run.

"Many ‘eco-products’ want people to believe they are 100% environmentally friendly," Julia said. "It's all smoke and mirrors." This team is having none of it. Their company begins with a big promise and delivers on it.

Alexis smiles, a little tired, which is understandable. He said that at various points they felt that this whole effort was "completely delusional." The sheer scope of the problem, the massive, unending piles of waste generated daily and dumped everywhere is enough to cause anyone to feel hopeless.

They went ahead anyway. As a result, the team created quite a high standard of products. "We were very proud of our progress," Alexis said.

Perhaps one of the team's greatest strengths was that they knew what they did well, and where they were weak. That kind of transparency allows them to identify where they needed help and what kind of expertise they required to keep improving. That's an uncommon trait among entrepreneurial firms, and the lack of it can torpedo otherwise superb ideas.

They knew that one of their primary markets, if not THE primary market would be the tourism industry, particularly at the higher end. Forward-thinking hotels and bush camps are increasingly sensitive to savvy tourists' demand that they leave less of a mark on the environment and take more steps to reduce impact.

For example, on my current trip to the Serengeti, Ngorongoro Crater and Tarangire National Forest, I was a guest at four Lemala properties, a company which has fully embraced the no-plastic model. To see more about how Dunia's work dovetails so perfectly into the very important model of sustainability for this company (and others like it) please visit this page.

Julia told me that Dunia has also designed for Lake Natrone tented camp, Asilia, Nyumbani camps and others.

For those of us who travel here and who are looking to make better choices about tourism companies who are reducing their environmental impact, it's a differentiator to see whether or not those camps are making this kind of investment. When you and I as travelers demand that these camps invest in this kind of game-changing product, we have the power to help further this kind of work.

And then the world came to a sudden stop

Before 2020, tourism was burgeoning, the market looked promising. Then, of course, Covid. The bottom fell out of the tourism market.

Many, if not most, fledgling entrepreneurial companies had to face the same hard facts that Dunia's team did.

"We had two choices," Alexis said, leaning back into the pretty pouffes (made of garbage).

"Shut the door, or rethink the whole operation top to bottom.

"We chose rebirth, to come out the other side. So with that, the team buckled down and recommitted," he smiled, as though enjoying the memory.

Up to this point, the company had been keeping a low profile. Designers, friends, potential clients knew generally what was afoot, but had no idea what the end product would look like.

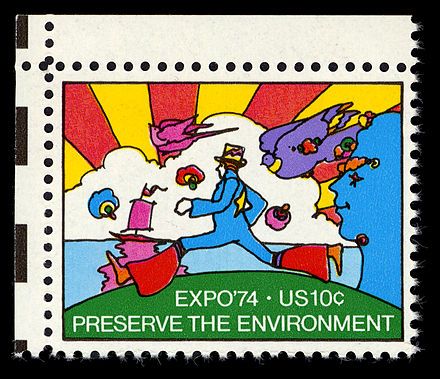

Perhaps, they thought, a bad, brightly-colored interpretation of a Peter Max piece from the Seventies. Interestingly, Max did create a postage stamp which, in that unfortunate way that few were attending fifty years ago, spoke to what Dunia Designs is trying so very hard to do today:

Their launch happily coincided with the general reopening of the Tanzanian society after lockdown. They had thrown themselves headfirst and hearts in their throats to prepare.

Nobody outside the company was prepared for what they saw on launch night, which was in spring of 2020, 21 November.

Julia and Alexis regaled me with stories about the preparation, which in every way possible had to vastly exceed expectations.

"This was an 11th round swing," Alexis grinned, one chance to win the match. The whole world had been on pause while their team was working feverishly to produce eye-popping, top-quality products that no one could possibly have anticipated.

Julia explained that it was a huge gamble, a single moment where they could catch up.

"We did what nobody else does," Julia said. "We couldn't NOT continue. We doubled down, hours and hours of creating and shooting; it had to be believable. We wanted to prove you could take low-grade waste with no value, and create beautiful, high-value products. We were up until three a.m. painting pots!"

Launch night was held in a beautiful facility Alexis had designed, which was even better.

To get a fun idea of what that looked like and how it went, please see this video clip.

Julia told me that the launch was ten times better than the showroom, and was an astonishing success.

People were completely blown away, precisely as I was when Julia told me that the gorgeous pieces that I was looking at started out in a garbage dump. Now that I know the backstory behind this furniture, for my part those pieces are even more beautiful.

The team had, in effect, faked it 'til they made it. The excellent designs, the colors, the imaginative presentation and the solid quality truly appeal to the growing insistence on quality not at the expense of, but in protection of, the environment.

"We can now focus on the business model," Julia said. Herein is where so many well-intentioned companies fail badly. It has to be a profitable business and the plan needs to work. They have already shown it can. Meaning well isn't enough. You have to turn a profit, grow, employ people and expand.

"We're now looking at investors, opportunities in Europe to expand this model," she added.

Every single facility that gets built reduces plastic garbage. Every bit of plastic garbage turned into beautiful, functional furniture solves multiple problems at the same time. More people are employed, more trees are preserved, more CO2 emissions are reduced by the trees which are left to grow and flourish.

As Alexis explained, a fair few folks are doing similar things. However, Dunia takes it several steps further. Every bit of their product is used, including plastic shavings which are turned into pillow and ottoman stuffing.

"We push the boat further," Alexi said.

There has to be an entire life cycle plan, and a way to build what Julia refers to as a "circular economy." As they focus heavily on the brand and the standards for which Dunia is already recognized, they now have to plan to train others to that standard as they expand.

As they increase demand for this furniture, that also creates an economy. Their Tanzanian template can, theoretically, be replicated. They're looking to create a scalable business where there is a demand.

Before we wrapped the interview, Julia walked me around the showroom so that I could take a few more photos. She explained that one of the longer-term goals is that as the business grows, to continue to invest in R&D to increase the scope of what the product can do. Then produce it even more efficiently, reducing the price and making it more accessible.

To that then here's just one example. There are millions of cheap, Chinese plastic chairs all over Africa. The market is flooded with them. They break easily, and invariably end up as part of the plastic problem. Providing everyday people, villagers, you and me with an affordable, quality, long-lasting product line has far-reaching implications.

Better products, less waste, less garbage, more trees, more employment. A circular economy. A sustainable one. And a better future.

Comments powered by Talkyard.