The phone call came in late in the afternoon.

“It’s about Peter.”

As soon as I heard her voice, thick with tears, I knew. My brother had committed suicide.

My big brother, 62, had popped a handful of pills, downed those with half a bottle of Tequila, and gone to sleep in his Jeep right in front of her house.

His suicide note read, “I only wanted to make you happy.”

So he left a dead body as a gift in front of her house, not unlike a cat will drop a dead mouse on the front step. Unlike the cat, my brother intended to punish her, the world, his friends, his family (me) and anyone else he felt had done him wrong.

He succeeded.

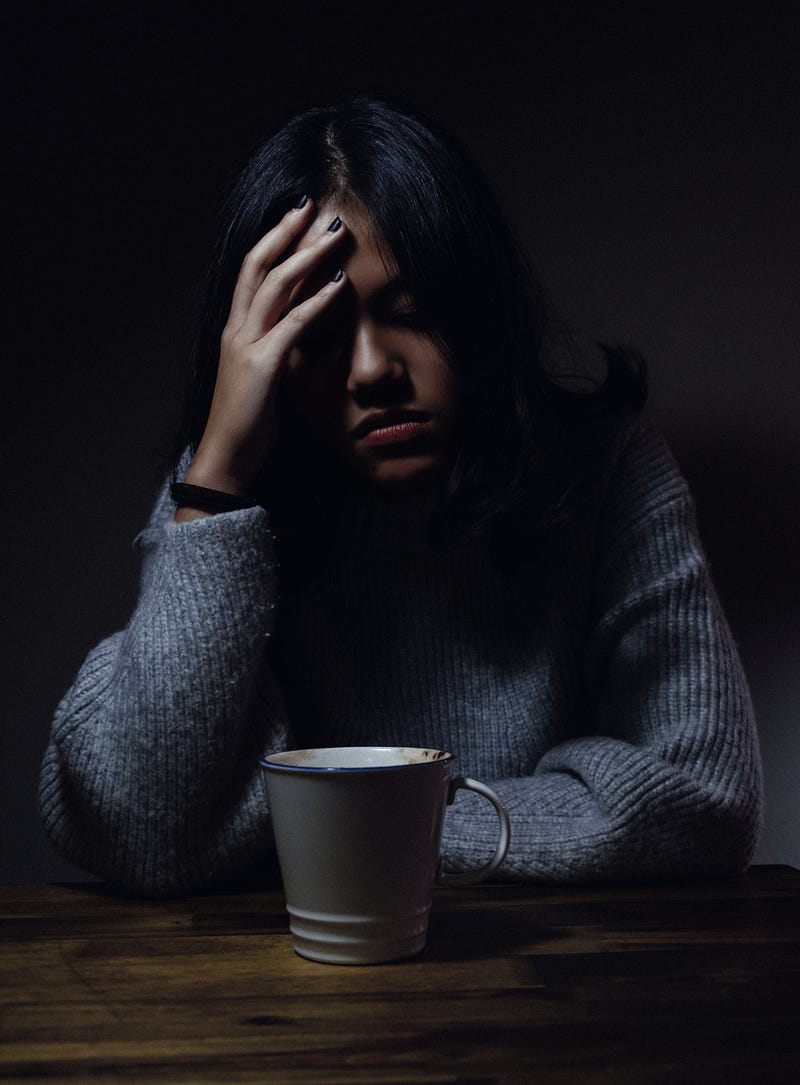

A Tsunami Wave of Hurt

The tsunami wave of heartbreak and hurt that a suicide slams into the lives of those affected is utterly unpredictable. Until a family member or a close friend takes their life, it’s impossible to have empathy for someone dealing with this kind of loss.

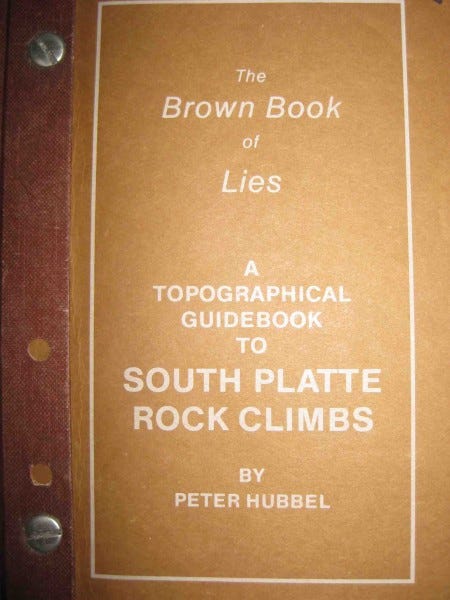

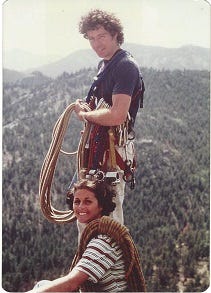

Peter had been an uber competent climber in Colorado, the author of some six books that he painstakingly developed over years of hiking to remote rock in the South Platte long before anyone else bothered to work that hard to find new routes. He was the quintessential climber: tall, lean, sinewy, determined, focused and talented.

He was also slightly mad. While that moniker might apply to many who climb (and do other extreme sports like I do, my hand is up) my brother was in some ways certifiable. At times immensely kind and generous, at others vicious and abusive, he embodied that dichotomy of extremes that marks many who struggle with bipolar disease.

It Starts Young

Peter had always been rebellious. Sent to military school in his early years due to behavioral problems by a grandfather who had been a colonel in World War I, Peter at first succeeded, then succumbed to drugs. In the late sixties and early seventies the drug culture in Florida had permeated every school, including military academies. By the time he got back home, he was badly hooked on amphetamines. He became a dealer, dropped out of high school and struggled to find work. He became an alcoholic and experimented with every kind of drug.

Yet, as is the case for so many dealing with mental illness, Peter was brilliant. Gifted with a high IQ, he was bored in school. A superb artist, talented writer and natural athlete, he had an abundance of abilities and no wherewithal to control his impulses. Drugs addled and abused his brain, and cost him cognitive skills. He was unable to control his rage, which caused him to get into fights with bosses and supervisors. He turned his artistic and problem-solving skills to construction. He became known for fine finishing work, for which he never charged enough to keep his head above financial waters. He didn’t know how to value his competence enough to support himself.

The Muddled Picture of Mental Illness

Because of the raft of recent shootings, mental illness has been identified as an “enemy” without much thought to what that actually looks like. My big brother was mentally ill, but he didn’t own, nor did he seek to own a gun. The only “gun” Peter owned was the invisible one he held to his own head for most of his life. He felt inadequate, unloved (although he was widely admired and liked), and bitter about how life had treated him. Who knows where such feelings come from? My parents lent or gave him thousands of dollars for nursing school, in which he excelled until he punched a doctor in the mouth over a disagreement. They lent him money to pay for broken down Jeeps and vans that he used to cart people into the high hills when he decided to start a climbing business. They gave him money and moral support when he started a gear business called Rhyno Gear. His creative ideas were sometimes picked up or stolen outright by huge gear manufacturers. He didn’t know how to protect his inventions. He often sewed his own clothing, with hands that crafted the cloth into near-perfect pieces. He was a genius in many ways.

He even got into composing music. His drawings of the eagles and the mountains evoked his love of the one place where he found sanity: the high country, where the only noise he heard was the wind as he hung dangling from difficult holds.

I Had No Idea

I perused my big brother’s art collection, listened to his music and admired the many photos of rock antics as we mingled at his wake some six months after Peter’s suicide. His climbing buddies had organized the gathering in Rocky Mountain National Park, a favorite haunt of my brother’s. The one and only time I had ever climbed, it had been in this park with Peter, some forty years prior. One of the few photos I possess of us together shows us at the top of the 5.9 crack, my first, which had torn my hands to shreds.

Typical of my brother, he had started me on some near-impossible task, trusting that I had the moxie to get to the top. I did. I didn’t fall in love with climbing. I did fall in love with other extreme sports, which Peter admired. But his love was the rock. It loved him back.

Peter’s wake allowed me to learn who my brother had become. Before that wake, my experience of Peter was largely made up of his insistent demands for money I didn’t possess. Stories of his failures and fights. Dropping out of this or that venture. The girlfriends who would call in tears, wanting advice on how to “fix” my big brother. Peter’s draining our aged parents’ bank accounts to pay for concert tickets and trips to go climbing. So much unhappy news.

The Other Side of the Story

During the wake, I heard tales of my brother’s heroism. He had saved the lives of two people who had gone off a mountain highway into a stream. He pulled both out, did CPR, and attended to their wounds before calling 911. By the time the police and ambulance arrived those people were stable and ready for transporting to the hospital. Just as the ambo came around the corner, my brother melted silently into the forest. Not many know that story. I sure didn’t. It was a revelation.

Others spoke of my brother as a father figure, a mentor. Their admiration for a man I hardly knew made me cry. I never knew this guy. I only knew a deeply troubled, perpetually angry man who couldn’t find a way in the world, whose perceptions of it colored his thinking such that he struggled to find a place in society. The women who loved him had their banking and emotional bank accounts drained, but they loved him passionately. If only, they said, if only enough love could fix him. It couldn’t. Peter hated himself.

It Takes a Wake to Wake You Up to a Family Member

After being estranged from my brother (over money, of course) for decades, I had been isolated from the man my brother had become. Still troubled, in some ways perhaps even more angry, as he aged and parts of his body didn’t support him the way he was accustomed to. Decades of smoking, skin cancer from extreme sun exposure, and the cumulative effects of poor habits which cost him his teeth had a terrible effect on his ego. The last time I saw him, we had a meeting about the family inheritance. The man who walked into the restaurant, barely eighteen months older than I am, looked thirty years older. It was a visual shock. Reading my face, Peter laughed. “Yeah, I know.” he grinned with that endearing, impish way of his. “The high country can be rough on your vanity.”

The next time I saw Peter, he was on a slab at the morgue.

However, that heartbreak, which can cause you to stand dizzily on the edge of a black hole of grief, inviting you to come on in after your last family member, was greatly assuaged by those who had loved and adored my big brother. Most didn’t know he had a sister. None knew he had a son, who is now in his mid-forties. My brother died not knowing he had a grandson. Or that his son was the spitting image of him.

I kicked off the wake by telling tales of my brother’s antics on the farm growing up, I set the tone for celebration. The stories that followed fundamentally rewrote for me the story of my big brother’s life. I drove home from that event transformed, having been given an extraordinary gift: a far greater understanding of the man who was my big bro. Complex, messy, confusing, maddening, yet immensely competent in his own way, influential, gracious, generous. In other words, a whole — and messy — person, like everyone else.

We Simply Don’t Know

Peter wasn’t the only one in our family to deal with mental illness. I do too. So does Peter’s son, who, when I tracked him down, was doing time in a California jail for murderous assault. This young man’s son, now in the military, may also be at risk. Who knows if there is a genetic piece. Who cares. What I have learned through my brother’s suicide is that not only do we not really know, we may never know. What I do know is that labeling my big brother -or me, or his son, or anyone else- mentally ill is patently unfair and grotesque. That diagnosis places a person in the jail of public opinion, especially today as we demonize mental illness as the cause of mass shootings. I beg to differ. The broad-brush picture that term paints grossly underestimates the entirety of that person’s life, their gifts, their potential, and the lives they change for the better. Peter’s wake woke me up to the vastness of who my brother was which far outstripped any diagnosis. He was troubled, yes. But he changed, and even saved, many lives.

In a world quick to slap easy labels on people as a way to predict behavior, dictating that someone is “mentally ill” provides a panacea for the easily frightened. We want to put folks in handy boxes so that we can “deal with them.” However, to some degree, we’re all just a little mad. Witness road rage, going postal, running people off the road because we’re in a hurry. What’s normal about that? What’s normal about trolling someone until they also commit suicide like my big brother? Were we all to go through the standardized tests, perhaps most of us would end up with a similar diagnosis, given the stresses of today’s world.

Being a little crazy can be a good thing. Sometimes it helps us survive. Sometimes we don’t make it, like my big brother. Yet in his own way, Peter gave me a gift. His suicide, while devastating, eventually caused me to question my own reason for living. As the last member of my immediate family, I have a legacy to leave. I get to honor the live-out-loud way my big brother did on the rocks and crags and ice of the Rocky Mountains. Each time I leap out of an airplane, kayak an icy stream, or stand on top of a mountain, Peter laughs inside my head. I’m slightly mad. You betcha. My friends tell me that all the time. They’re right.

You need that to survive this crazy world. That’s not mentally ill. That’s just sucking the marrow out of life. Peter did it until he couldn’t any more. And that’s all right. I no longer know that anyone can define what normal is any more. Given that, who are we to stay who is or isn’t mentally ill in a world where a guy who can’t get a job sets up murderous bombs all over Austin? My brother had a worse diagnosis. But he saved lives.

And I have my slightly insane brother to thank in part for the slightly mad but marvelous life I live today. For my money, a little madness is a good thing.

Comments powered by Talkyard.