In the seminal book The Power of Habit, author Charles Duhigg, the author outlines where and how habits evolve, and explains why they are so useful to the human experience.

He also goes into the detail about how to break what he calls a “keystone habit,” like smoking or overeating. When we are able to rewire the circuitry to change an addictive habit, it becomes far easier to break others.

When I was barely 16, I started smoking. As with most things I take up, I threw myself into this addiction, ending up at 19 with a five-pack-a-day habit. I started smoking because I grew up in a sexually-abusive family. Its purpose was to give me a way to dissipate anxiety, simply a repetitive movement which took my mind off pain.

Five packs a day.

Imagine. The moment I woke up, I lit up. I burned holes into the top of my toilet while a cigarette smouldered during my showers. I burned holes in my clothing and my skin and my carpet and nearly scorched my dog. It didn’t take long at that level of consumption for my lungs to be consumed. I had a horrible, wet, hacking cough that dominated my days. At 19.

So I quit, cold turkey. The day I quit was the day I began running around my local middle-school track. I had a severed Achilles’ tendon. The cast had just been removed. My doctor, a short, square man with a bulldog mug, (who also smoked like a chimney) informed me that I would always walk with a limp, and never be able to quit smoking.

I proved him dead wrong on both counts. Willy Steele died young, a doctor who couldn’t take care of his own health. I began my career as a compulsive exerciser. Because the brain liked the distraction, and the heart couldn’t handle the pain. I had to find something else.

As anyone who is running hard from pain can explain, we morph from one compulsion to another, as perfectly outlined in Markham Heid’s Medium piece. In some cases we morph to an initially healthy activity, which in my case was going from being a compulsive smoker to an over-exerciser.

However after some horrific experiences that I’ve outlined elsewhere I found myself seeking relief from my hurts and anxiety through eating disorders. And exercise. And compulsive spending. And. And. And.

Habit energies, whether they are positive or negative, sometimes serve a terribly important function. For example, after we get through the grind of learning how to drive, the normal actions/reactions take over (okay, let’s not go into distracted driving, which is another habit and a STUPID one). Driving becomes largely instinctual, and for the most part, assuming we’re attending to what we’re doing, we don’t have to mull over every moment in our cars.

It’s almost like breathing. I engaged in my eating disorders while driving, which is not only monumentally foolish but dangerous as hell. At least I kept my eyes on the road, but it sure would have been one unholy mess if I had rear-ended someone with several dozen Krispy Kremes sitting open on my front seat.

So much of what Medium’s self-appointed, self-help gurus of all ages love to do is give us lengthy listicles of how-tos make our lives better. The Nine Things You Need to Do To Be a Better ________. Frankly, a great deal of it is bullshit. Because — and again, I include myself here big time-- most of us are talkers rather than doers. Becoming a true practitioner takes years of effort and in no small way requires that we do a deep dive within first.

I might posit that rather than try to follow someone else’s list, it makes more sense to become a serious student of one’s own habits. What do you do regularly and what does it get you? What is your why?

Habits become destructive when we lapse into relative comatose comfort as we go through mindless routines. We’re not present because the mind knows what’s coming (the way you make the bed, how you set up your Kuerig, feed the dog). That way it can turn its attention to other things, as it deems necessary. When faced with mindless, horrific pain — at any stage in life — the brain will do its best to find a way to derail the hurt.

Most of us have no clue that this is going on. The habits of drug abuse or alcoholism are well-chronicled, but as Heid’s article points out, Columbia University professor Jeffrey Sachs says

“My argument is that the U.S. is suffering an epidemic of addictions, and that these addictions are leaving a rising portion of American society unhappy,” he writes.

I would further posit that the addictions are borne of pain, so we engage in the distractions to the point of further pain as an avoidance technique. There is nothing “well” about forcing ourselves to do extreme yoga (which is intended to be peaceful) or extreme Tough Mudders or extreme any damned thing. There is nothing “well” about beating your body to a pulp in endurance running when what is truly driving that behavior is sexual abuse, or deep anxiety, or loneliness. Pain is pain is pain. Until we face down the demon that drives us we will subject ourselves to even more pain to avoid the initial pain, the shame, whatever it is that is so deeply hurtful.

It’s the very definition of madness. My god have I been down that road my entire life. My hand is way, way, way up here. If there is any “well” here, it’s the well of pain that we so desperately wish to avoid gazing into. Because the “abyss gazes back.” On far too many occasions, I have very nearly done a header into that abyss.

Habit energy can cause us to do some pretty hare-brained things. As a lifelong gym member, like many folks, I have a favorite locker. It’s rarely occupied, so in that silly way that we exert our territorial imperative, I think of locker 267 as mine. So when someone else (who has every right to it) occupies it, I’m a bit flustered.

One day I came into the gym in a bit of a hurry. “My” locker was in use, so I had to scootch over to a different one. That threw off my routine. I got into a lively conversation with someone else as I was disrobing. That further threw off my carefully-constructed, 45-year habitual dressing process. I threw on this, that and the other, popped in my ear buds and strode out onto the gym floor at speed.

About ten feet into the gym there was a large wall mirror. As I hurried by I happened to glance at the specter of a half-naked woman, her boobs bouncing merrily in broad daylight. I stopped in shock.

Um.

Those look like my boobs.

HOLY SHIT THOSE ARE MY BOOBS.

Let’s just say the gentlemen of the gym got a little more than they had bargained for that particular workout session.

I shot back to the locker room, consumed in laughter, face bright red. It took me about fifteen minutes to get the gumption back up to return to the gym floor.

The same kind of blind mindlessness accompanies many of our habits, whether driving or at work or in our relationships. The brain is totally on auto pilot, until some kind of shock intervenes.

Not just the shock of embarrassment. Also the shock of overuse injury, exhaustion, burnout, the reality check that overexercising actually reduces muscle. Any one of a thousand different ways that the body and the brain try to wave bright yellow semaphore flags at us that we’re headed for serious trouble.

Problem is, when we don’t dance with the demons within, those demons will simply drive us to something else for distraction from the pain and anxiety. Until we collapse or die. We must have relief. For some, like my big brother, that relief comes with suicide. Demons 1, big brother Peter, 0.

From Heid’s story to this point:

Some people also rely on exercise or diet to regulate their emotions. “People use these things as a way to respond to feeling unhappy or anxious, or other forms of emotional distress,” says Pamela Keel, a professor of psychology at Florida State University. “But these don’t address the original source of the distress, so these are quick fixes that set you up for a vicious cycle.”

The temporary feel-good that you and I might get from a marathon swiftly descends into nowhere near enough. So then we double the distance. Or increase our weights. Or or or or. Nothing satisfies. It never will. It can’t.

The mind isn’t designed this way.

Keel’s use of the word “some” completely understates how widespread this problem is. If we were to list all the addictions that we as a society engage in- and that includes the so-called “good” addictions like exercise, my guess is that the phenomenon touches every single one of us. Either we’re directly engaged (and an addiction to self-help most assuredly satisfies the criteria) or someone close to us is in the throes. My ex-BF was consumed both by work and exercise.

If Medium writers are any indication, we are all affected. Or, infected, as the case may be. This is not a judgement. Just an observation. Because as the poster child for a lifetime of avoidance habits, my fellow practitioners are very easy to spot.

What’s even more troubling, and I can only speak for myself here, is that simply having noticed, and become fully aware of, my habit energies is largely meaningless. It’s like the guy who diligently reads the Bible and then goes out to rape, burn, pillage. The Mafia, for example. Are you listening, Catholic Church?

He knows but he cannot do.

That I can march out onto the gym floor with the headlights on full beam without the slightest knowledge is testament just to how completely and utterly asleep most of us are, aided (and abetted) by our devices, our determination to submerge our pain and anxiety under endless layers of doing-ness.

It’s not just being distracted. It’s being almost totally out of body. Why? Because the body contains so much pain that I can’t bear to be in it.

However, I have slowly but surely been able to not only shift my understanding of my why (Why am I striving so hard? Why I am pushing so hard? What am I refusing to look at? What is the source of all this running?), I have also slowly but surely been able to redirect the habit energies. I write instead of run eight miles. I run three, but produce more articles, which makes me money, and gives me pleasure. I love to write. It feeds my soul and in very important ways allows me to waltz with what is at times wicked inside. There is a truce brewing here.

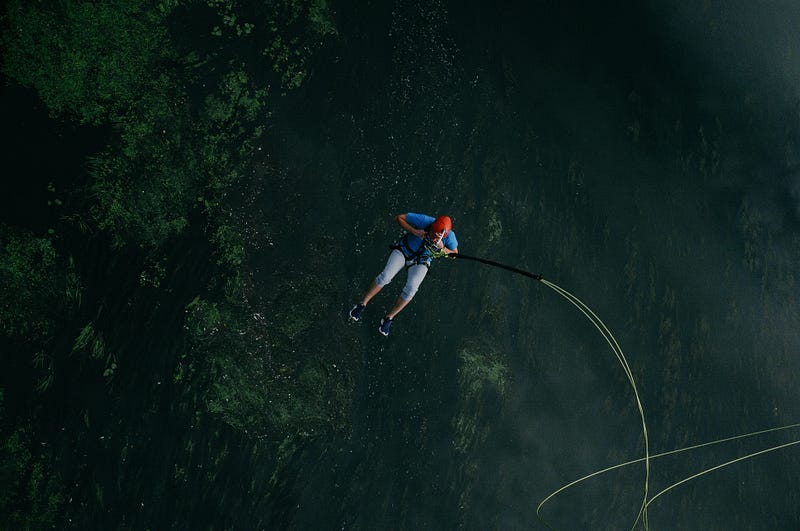

I take adventure trips instead of hiding in the bathroom, forcing myself to toss my guts. Untold benefits of that, and besides, I eat normally now. I feed the engine that allows me to adventure.

I’ve backed off over-training in exchange for what works for me right now, this body, this age. I still push but not to the point of injury. What on earth am I punishing myself for anyway? I love to move. Sweat. I don’t need to injure myself. Nobody hands out hero buttons for killing yourself slowly at work, at play, at home. So why are we killing ourselves slowly with all this extremity?

Aye, there’s the rub. We are getting to the why.

I still have compulsive habit energies. What’s different, and this is the absolute hardest part, is that I have chosen to face my demons down. I’ve engaged in the exceptionally difficult process in the book Unlearn Your Pain by Dr. Howard Schubiner. The first written exercise was that I had to write down every single awful thing that has happened to cause me pain, shame, guilt, fear. To say that this unearthed a great many corpses, including many I had forgotten (my young brain was smart enough to file a goodly amount of this shit under lock and key for 44 years) is one hell of an understatement.

This process is not for the faint of heart. I got to that part and was sidelined in real distress for three weeks straight. I couldn’t complete the exercise. This is how toxic these memories are that drive us. However if I want my freedom from pain, both physical and emotional, I will finish this.

I must finish this or it will by god finish me. Like it finished my big brother.

It’s a 28-day program, and I am now three weeks behind. If I weren’t more aware, I’d be berating myself for not finishing the book on time. You see how insidious this is. I have to be the best at finishing this 28-day program.

WHY, FOR GOD’S SAKE?

Precisely.

What am I trying to prove? That my dad was wrong when he called me a loser. That he was wrong when he said I’d never amount to anything. Sound familiar?

Each and every one of us without exception carries pain of some kind. Some of us far more than others. There is no such thing as a pain-free existence. However in our search to assuage that pain, all too often we bury it under layers of denial, protective behaviors and a habit of running as hard as we possibly can away from the agony of self-hate, self-doubt, self-revulsion.

In a society that denigrates mourning, that doesn’t encourage tears, we bury what we need to face. Why do we have movies about zombies that eat our living selves? Here’s my take: every one of them represents an evil, painful memory that threatens to eat us alive. What a terrific analogy. No wonder we’d prefer they stay buried. It’s a perfect metaphor for what terrifies us. We are scared to death of that which we buried coming up and consuming us.

The problem is that this is precisely what those memories and the associated painful feelings are doing anyway.

That is our humanity. But if there is going to be hope for you or me or any other rape and abuse victim, child of alcoholics, those of us whose parents blame us for a spouse’s death, the shame we feel for simply being born, whatever the incident may be, we have to stand in front of that pain, that guilt, that shame and tell the truth.

People tell me I have a lot of courage to do the wild-ass adventures I do.

Let me be very clear: it is vastly easier for me to stand on a precipice and hurl my aging body into infinity than to do the work this book demands of me.

In the superb 1992 movie A Few Good Men, a rookie lawyer played by Tom Cruise pushes Colonel Nathan Jessup (played by a typically intense Jack Nicholson) to spill the beans on an order that caused the death of a Marine. His response, which echoes down through movie history, is

“YOU CAN’T HANDLE THE TRUTH.”

For most of us, that is the truth.

That is why we are consumed by our addictions. We’re avoiding what we feel is the truth: that we’re not lovable, that we are responsible for being raped, that it’s our fault a parent died, everything is our fault. The list is endless.

The real truth, which takes enormous courage to reveal, is that in most cases, it wasn’t our fault at all. If we teased out the salient details in so many cases, the offender was probably the one at fault. Not us. But we bear the burden, we bear the pain, guilt, shame and anxiety that all those emotions cause. Especially for kids, who own the problem when a parent is troubled and incapable of handling their own pain.

No 100-mile endurance race in Leadville will ever get the lead out of my feet if I am hoping to rise. No gym routine, no horseback ride, no extreme adventure is ever going to give me peace. The only way I get peace is to do this work.

I can handle the truth.

I’ve spent a lifetime running full tilt from the pain of alcoholic parents, a sexual predator of a brother, multiple rapes in the military, a history of abusive and emotionally distant men. I have blamed myself for every single one of these events. As if I could have done anything about most of them.

If I want something different I have change my habits. Not just any habit. THIS habit.

Back in my thirties I wrote a poem called Dancing in the Audience. It was prophetic. Half a life later, I still struggle with being my own best friend instead of my worst critic.

Badass, as one Medium writer pointed out, is a woefully-overused word. All too often it refers to the extremes to which we are beating up our bodies. How many extra hours we’re working. In one way or another demonstrating our (supposed) mastery over the self through self-imposed Spartan routines.

I believe that we use this term because we want to believe that someone else out there has it all together ( I sure as shit don’t). Someone out there has handled their demons (I sure as shit haven’t).

So I would argue otherwise. As one who has lived a so-called badass life by that very definition, all this has proven to me is how little courage I truly possess.

It’s a lot easier to run from what threatens to pierce my heart.

In the final fight scene of The Hobbit, Battle of the Five Armies, the Dwarf King Thorin Oakenshield is fighting for his life against his sworn enemy, Azog. The massive orc has him on his back, on the ice, with a spear pointed into his chest. For Oakenshield to prevail, he has to let Azog’s spear strike the killing blow. That allows him just enough distraction and time to kill the demon. (The 3.22 minute mark)

While Oakenshield dies, the way I experience this metaphor is that we have to release both what hounds us and ourselves from the pain this causes. Only then are we free.

Fighting my demons is no less an effort. To me, this is the ultimate internal battle. Mine are no prettier than Azog, no less vicious. To win this battle I have to surrender first. Face them all. One by one. If the demons are to die, then the person those demons control has to die, too. That person is a lie, construct, because she is guilty as charged.

No she isn’t. Not as a four-year-old. Not as ten-year-old. Not as a twelve-year-old. Not as a 23-year-old rape victim. It wasn’t my fault. And I refuse to carry the burden of others’ evil.

But as long as I allow those demons to define me, that version of myself lives on. By letting that dishonest version of who I am die, so does the demon.

By releasing her and the demon that has tracked her all these years, I am free.

With a hat’s off to my Medium friend Ann Litts, this is what it’s going to look like:

I will be battered on this journey, but far less so than if I keep running. For me there is no courage in continuing to do epic adventure travel if my underlying prime why is to try to avoid emotional pain.

And finally, here’s an even greater truth, which is devilishly hard to sidestep: I believe in my heart of hearts that one of the reasons I keep getting injured or sick on my trips is that the Universe in all its wisdom is telling me to Do. The. Work.

Oh, baby, that’s one helluva tap dance to embrace.

Go inside. Call them out. Face them down. And kill the lousy bastards for the lies they are. For they are lies, just as the internal hounds of hell that tell you and everyone else that we are unworthy are lies.

So what’s the demon-killer? Forgiveness. Mercy. Self-love. Acceptance. Humor, my god, humor. The ability to see our offenders as flawed, damaged, and also driven by demons that they couldn’t, or chose not to control.

Ultimately, love. Because most of us would never subject a beloved child to the internal horrors we heap upon ourselves. If we couldn’t countenance this, then kindly, why on earth do we countenance allowing those horrors to hound us?

Indeed.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve got some demons to kill. A listicle won’t do it.

But love will.

Comments powered by Talkyard.